Category Archives: WHAT TO DRAW IN YOUR SKETCHBOOK

ASSIGNMENTS I HAVE MADE FOR MY DRAWING STUDENTS AND WHICH I DREW IN MY OWN SKETCHBOOKS

BASIC PROPORTIONS OF THE HUMAN BODY

The ancient Greeks studied real human proportions in order to make their statues more ideal. The Roman architect, Vitruvius in the 1st century BC also studied the relationships of the human body and used these in his buildings. Leonardo DaVinci is known for his “Vitruvian Man” which he got from Vitruvius’ writings. He used the human head as his comparison point and based his measurements on an ideal proportion of 8 heads tall. This is pretty convenient in that the figure is 4 heads tall at the lower part of the torso, and can be divided into quarter points at the chest and knees. The arms are usually divided into half at the elbow as will the legs just below the knee.

But the human body is different in everyone. Most artists now say that the figure is 7 ½ heads tall, as in the following example. This was developed by a 19th century anatomist, Dr. Paul Richer. The half-way mark is just a little below the pubic bone, and the third head is at the belly button.

In the example below, see that the human body is basically 7 ½ heads or 7 heads tall, based on the length of the head. Males and females are the same, which means, of course, that the female head is smaller than the male. See where the arms come to – the waist, the knee, the pelvic bones. This is only a guide, because you have to look closely at your model to see his/her true proportions.

The illustration below is taken from Anatomy and Drawing by Victor Perard, 13th printing 1948 – one of my most prized drawing books.

If you really want to learn how to draw the human body, draw from photos, magazine pictures, and any time you’re sitting in a waiting room with others. Keep your sketchbook and pencil handy. One caveat, however: If you draw from fashion models, realize that the rule of 7 1/2 heads does not apply. Fashion illustrators and photographers enlongate the female figure so as to make the clothes look better. CHECK IT OUT!

DRAWING PORTRAITS FROM A GRID

Using a grid is the easy way to reproduce a photograph, and IT’S NOT TRACING! Renaissance artists such as Durer and da Vinci used a standup grid to get correct proportions of a live subject. In my last portrait drawing class, I showed my students how to use a 1″ grid on an 8×10″ photograph to draw their own self-portraits. Here is the result from one of my students, Linda Keesee. She placed the grid on the photograph and made another 1″ grid on her drawing paper, then drew from the photo square by square to complete the final product. If you want to enlarge a photograph, either use a 1″ grid on the photo and a 2″ grid on your drawing paper, or a 1/2″ grid on the photo and a 1″ grid on the paper. Either way, your drawing will be twice the size of the photograph.

Of course, if you’re confident of your ability, you could skip the grid and draw free hand, but that could get you in trouble! Also, some of you who have done this before might like to try the alternate method – making an x on the corners and dividing each section equally. If you do this, you’ll need to trace your photo and use the grid on the tracing.

DRAWING PORTRAITS – FEATURES OF THE FACE – EARS

You may think the ear is hard to draw because of its intricate folds and wrinkles, but if you just get the basic shape right, it’s not that difficult. If the head is drawn straight on, like a wanted ad, you can hardly see the ear, especially if hair covers it. The problem comes when the head is seen in 3/4 view, or in profile. That’s when you need to look carefully at the ear’s inner and outer shapes. Here is an example of the ear seen in profile:

Here is an older man’s portrait.

Here is an older man’s portrait.

And here is a young girls’ portrait

Other examples:

DRAWING PORTRAITS – FEATURES OF THE FACE: the nose

Noses are very much unique to the individual. They can be straight, crooked, with a big bump in it, have widely flared nostrils, slim, or large. My mother had what she called a “roman nose — it roamed all over her face!” Pay a lot of attention to the different shapes, angles, and planes of the nose. The bridge of the nose is a bone, while the edges are cartilage. There is a round ball at the end of the nose, and the flares of nostrils are wedge shapes. The overall shape of the nose is narrow at the top, and wide at the base.

After the structural lines have been made, shading the nose is the best way to define the form. If you’re drawing the nose from a front view, the only way to show the form is by the subtle variations of lights and darks. Don’t draw lines on the side of the nose. The darkest shadows lie next to the bridge. Drawing noses from a profile view is easier, because then you can ouline the nose. Nostril openings face down and should not be overstated. Because the tip of the nose is spherical, it usually has a highlight. Look carefully at the light source and the reflected light. The nose will also cast a shadow beneath it.

Here are some examples:

This example is from the Watercolor Artist magazine of June 1212.

DRAWING PORTRAITS – THE FEATURES OF THE FACE

DRAWING THE MOUTH AND LIPS

One of the most expressive features of the face is the mouth — it can express a person’s age, gender, ethnicity, and emotion. Everyone’s mouth is different, so look for the uniqueness in your model’s mouth and lips. Generally speaking, however, the top lip is slimmer and more in shadow than the lower lip, because it recedes slightly backward. Full lips look youthful, while thin lips look older. The top lip has a little indentation in the middle and slants downward toward the edge of the mouth. The lower lip seems to have two ovoid shapes on either side. See example below:

Be careful if you include the teeth. You don’t want them to look like pickets in a fence. You can define an adult’s teeth by showing the gums at the top and a division at the bottom. The teeth are shaded more as they recede into the mouth. Children’s teeth are usually seen as individual, since their’s are not fully developed.

Be aware of the subtle shading of the lips. There is usually a slight highlight on the lower lip. Watch especially what happens in a three-quarter and profile view. Remember also, that there is some shading under the mouth. Since the lips protrude slightly from the face, there are several tonal variations in the skin and surrounding areas. So be observant, and practice in your sketchbook.

DRAWING PORTRAITS – THE FEATURES OF THE FACE

Once you have the correct proportions of the face, and have considered the planes of the face as it turns away from the light, it’s time to put in the features of the face: the eyes, eyebrows, nose, ears, mouth. This is the time for careful observation, because even though everyone’s features are close to the same, it is the little differences that cause you to draw a true likeness. Here are some pointers.

THE EYE: The eyeball fits into the eye socket and the eyelids wrap over the eyeballs. The pupil is quite large in dim light, and smaller in bright light. The iris is darker under the eyelid because of the overlapping shape. Be sure that the eyeballs are placed in the same position in the eye socket, so the model doesn’t look cross-eyed, and make sure that the highlights in the iris and the pupils are in the same place. Light colored eyes usually have a darker rim (limbus) around the iris. Eyebrows vary from individual to individual and help to contribute to a correct likeness. As the face turns or tilts, the eyeballs can be foreshortened. Don’t forget the tear duct. Pay attention to the lower eyelid, the wrinkles and shadows around the eye. Shadows are darker close to the nose — these shadows often give structure to the nose.

A lot of expression can be put into the placement of the eyeball — for instance, if surprise or fright is to be shown, the whites of the eyes can be seen around the eyeball. If the model is sleepy, uninterested, or even angry, the eyelids squeeze together – maybe even in a squint. Careful observation is necessary.

Don’t make the mistake of putting in lines for eyelashes — simply darken about the eye to suggest them. The eyelashes are thickest toward the outer corner. The lower lid has a mild highlight along it’s edge.

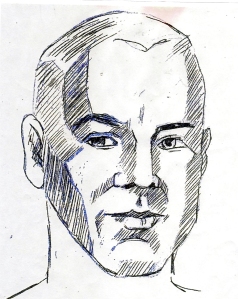

DRAWING PORTRAITS – THE PLANES OF THE FACE

Getting the correct proportions of the face you’re drawing is one thing, but what about shading the face so that it looks three dimensional? You need to think about the structure of the face as consisting of several planes that either catch the light or seen in shadows. Imagine that you are sculpting a head out of a big block of stone or clay. You have to remove chunks at first to shape the head, and then you have to chip away in slices — no curves as yet. You are modeling the form, which is what you need to do in drawing a portrait as well.

In your drawing, you will look at the planes to shade the portrait as it recedes into space. You can use hatching and cross-hatching to define the areas. Always remember one simple rule — what comes forward catches the light; what goes back is in shadow. So the nose is always in light, as is the forehead, the chin, and the cheeks to some degree. Darker values will be seen under the eyebrows, the nose, and the lower lip. Here is a diagram to illustrate.

DRAWING PORTRAITS – FORESHORTENING

Knowing about the basic proportions of the head is fine, but what happens when the artist doesn’t have a frontal view, or the head is tilted causing foreshortening? A bigger problem, of course. Actually, a profile view is easiest of all to draw because you have the negative space to help, and maybe because you only have one eye, one ear, one nostril, one-half of the lip to draw! At any rate, most people would not like to have their portrait done head on – like a wanted poster. The best view for portraits is a 3/4 view.

And if the head is tilted upward, or downward, the basic proportions of 1/3, or 1/2 no longer work. If the head tilts upward, you see more of the chin, neck, nostrils, etc. and less of the forehead. The proportional ‘thirds” diminish near the top of the head, and the nose appears above the lower part of the ear. If the head tilts downward, you will see more of the hair, the forehead and less of the eyes, lips and nose. The top “third” seems to be larger and the nose is below the lower part of the ear. Always remember to find the center line and the slant of the head. Notice the curves in the vertical and horizontal center lines. Here are some examples. Although not the best drawings in the world, you can see what happens in each case.

DRAWING PORTRAITS – BASIC PROPORTIONS

CURRENTLY, I AM TEACHING A PORTRAIT/FIGURE DRAWING CLASS AT THE MAUMELLE SENIOR WELLNESS CENTER. I AM SHARING SOME OF THE LESSONS ON MY BLOG.

WHEN YOU DRAW A PORTRAIT OR A FIGURE STUDY FROM LIFE, YOU HAVE TO HAVE A KNOWLEDGE OF PROPORTION – MEASUREMENT AND COMPARISON. EVERY PERSON IS DIFFERENT, BUT THERE ARE SOME SIMILARITIES – SOME BASIC PROPORTIONS THAT WILL HELP YOU GET A LIKENESS.

ALWAYS BEGIN WITH A SKETCH – USE YOUR EYE TO SKETCH THE SUBJECT LIGHTLY – THEN YOU CAN USE MEASUREMENT AND COMPARISONS TO BECOME MORE ACCURATE. KEEP IT SIMPLE AND LEARN TO USE OBSERVATION. BEGIN WITH A STANDARD LINE – A BENCHMARK, AS HEIGHT. MAKE LIGHT MARKS TO INDICATE THE TOP AND BOTTOM OF THE HEAD. DRAW A LITTLE BIT SMALLER THAN LIFE SIZE.

WE ARE TRYING TO DEPICT A 3 DIMENSIONAL SUBJECT ON A 2 DIMENSIONAL SHEET OF PAPER. IT HELPS TO THINK OF THE PICTURE PLANE AS AN INVISIBLE PANE OF GLASS BETWEEN YOU AND THE SUBJECT.

Start with basic oval shape. Draw lines to divide the shape in half vertically and horizontally. The eyes are located on the center line of the shape.

Measure – the width of five eyes for the width of the face and the length of seven eyes for the height.

Draw eyes on horizontal line with one eye width of space between.

Draw horizontal line halfway between eyes and chin, — this is the bottom of the nose and ears.

Mouth line is about a third of the way down from the nose line. The hair line is a third above the eyebrows.

Draw vertical lines down from the inside corner of the eyes to the nose line = the width of the bottom of the nose.

Lines from the center of the eyes drawn vertically place the edges of the mouth.

Eyebrows line up with the tops of the ears and the bottom of ears line up with bottom of nose.

Add neck and shoulder in cylinder and wedge forms.

PATCHWORK COUNTY: ANOTHER EXPERIMENT IN ABSTRACTION

In this abstracted 16 x 16″ landscape, I was trying to use one of the six basic value schemes mentioned by Edgar Whitney. The scheme was a little dark with a lot of light in medium values. I seldom use this value scheme; that’s why I wanted to try it. I also wanted to continue breaking up the picture plane into sections, but still be able to lead the eye movement to the center of interest (the barn in the upper right area). As usual, I worked out the value and color scheme in my sketchbook and decided to use a split-complementary color scheme: blue, red orange, orange, and yellow orange. The acrylic colors I used were Cadmium Orange, Hansa Yellow, Indian Yellow, Thalo Blue, Prussian Blue, Raw sienna, Burnt Sienna, Cadium Red Light and Titanium White. (At least, that’s what I think I used — hard to remember now!)

In this abstracted 16 x 16″ landscape, I was trying to use one of the six basic value schemes mentioned by Edgar Whitney. The scheme was a little dark with a lot of light in medium values. I seldom use this value scheme; that’s why I wanted to try it. I also wanted to continue breaking up the picture plane into sections, but still be able to lead the eye movement to the center of interest (the barn in the upper right area). As usual, I worked out the value and color scheme in my sketchbook and decided to use a split-complementary color scheme: blue, red orange, orange, and yellow orange. The acrylic colors I used were Cadmium Orange, Hansa Yellow, Indian Yellow, Thalo Blue, Prussian Blue, Raw sienna, Burnt Sienna, Cadium Red Light and Titanium White. (At least, that’s what I think I used — hard to remember now!)